Civico Museo d’Arte Orientale

Palazzetto Leo

Via San Sebastiano, 1

Trieste

+39 040 3220736

+39 040 6754068

museoarteorientale@comune.trieste.it

The Museum of Far Eastern Art is in the heart of Trieste, very close to Piazza Unità d’Italia, and it situated in a mid-eighteenth century patrician house called the palazzetto Leo after the eponymous Trieste family.

The last owner, the Countess Margherita Nugent, bequeathed the house to the city of Trieste in 1954. Since 2001, the building has been housing the Asian art collections of the Civic Museums of History and Art, including porcelain vases, prints and paintings, sculptures, silk dresses, weapons and musical instruments mainly from China and Japan.

The origin of the collection

As the main seaport of the Habsburg Empire and a landing for ships and people from distant places, Trieste has been a privileged center for the collection of non-European objects since the eighteenth century.

Naval officers, collectors, artists and wealthy families enriched municipal collections with numerous bequests and donations of Chinese and Japanese artifacts that had reached Trieste by sea (especially by the Austrian Lloyd steamships, among the first boats to cross the Suez Canal). Between the second half of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th they have formed many China-Japanese collections, supported by anthropological curiosity (surimono, netsuke and Chinese silks) and research of exotic pieces of furniture (porcelain vases and Ukiyo-e prints). These objects were in the houses of prominent families of Trieste (Caccia, Currò, Barzilai, Artelli, Sartorio, Piacere), intellectuals and collectors such as Carlo Zanella, Lloyd agent in Hong Kong, Mario Morpurgo de Nilma and most of all the Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian of Habsburg, who was also a passionate admirer of Chinese porcelain, and whose collection may be found in Trieste at Miramare Castle.

The museum tour

The first two rooms of the ground floor are devoted to temporary exhibitions. They evoke the Wünsch Chinese Cabinet, something between a museum and a curiosity shop that was characteristic in Trieste between 1840 and 1890. The third room houses a small but interesting collection of Gandhara sculptures from the 1st to the 4th century A.D., acquired during the Italian expedition to the Karakorum in 1954 headed by Ardito Desio, which also led to the first ascent to the summit of K2.

The first floor is entirely dedicated to the art of China. Two fundamental aspects of Chinese material culture, porcelain and silk, show millenniums of knowledge and craftsmanship and are illustrated by a nineteenth century collection of silk garments and by a selection of porcelain from the Song (960-1279), Yuan (1279-1368), Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties. The showcases of the main hall contain céladon (green jade coloured) vases from the 12th to the 14th century and blue-and-white porcelain. The latter dates back to a “golden age” of production during the Ming period, at the end of which the manufacture of this particular kind of pottery intensified greatly as cobalt – the essential element for blue – previously imported from Persia and the Middle East was also found in the Chinese territory.

Since the Qing dynasty, China has also increased production of polychrome porcelain models (the so-called famille verte and famille rose), some artifacts of which are here on display. The museum also houses some porcelain specimens of the so-called “blanc de Chine”, dating from Ming age until the late Qing era. The third room houses a selection of European and Italian pottery and porcelain in orientalist style, showing one of the many aspects assumed by the European engagement with Far Eastern cultures from the seventeenth century onwards.

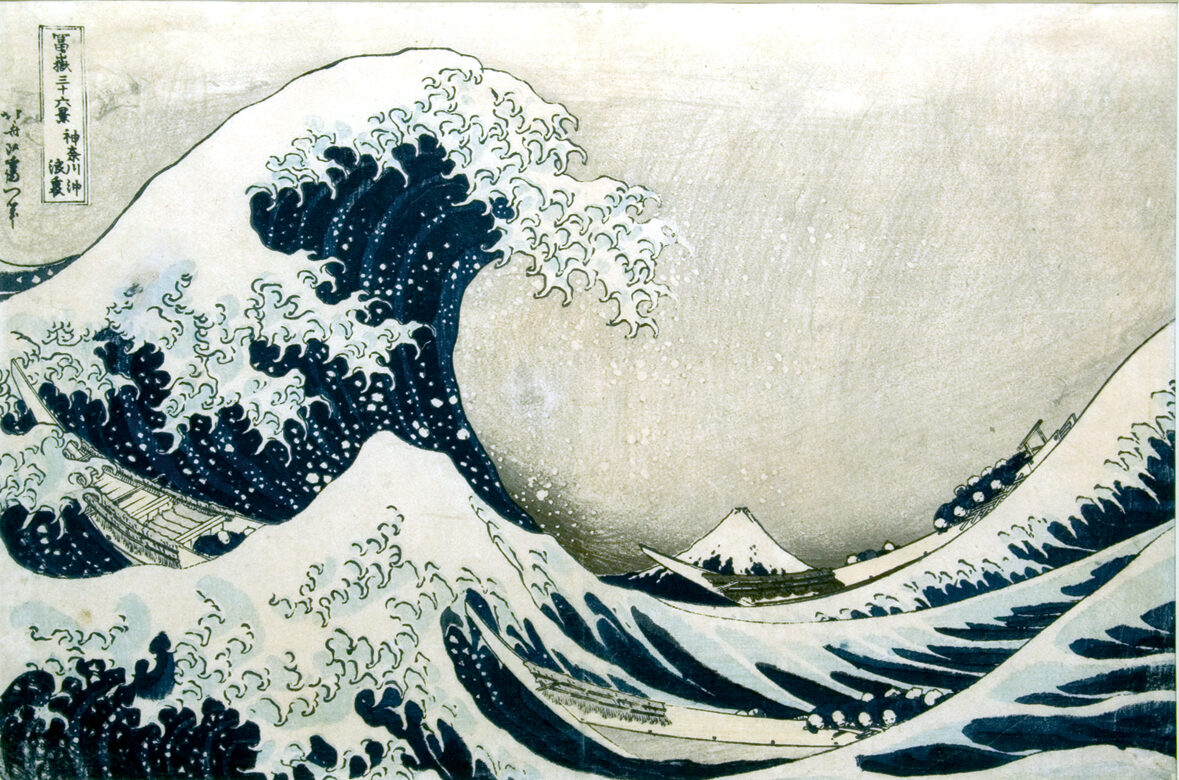

The second and the third floors feature objects from Japan belonging largely to the Edo or Tokugawa (1615-1868) and Meiji (1868-1912) eras. The second floor boasts a rich set of prints by artists including Utamaro, Hokusai, Hiroshige, Kunisada and many other masters of Ukiyo-e (“floating world”), which describe everyday life in all its aspects. This kind of art referred to a particular segment of Edo society – a middle class who grew up in an era of peace and prosperity – who wanted to enjoy pleasures offered by life. This joie de vivre is also evident in the love for precious artifacts made of ivory (netsuke), lacquer (like the writing boxes called suzuribako) and metal, and in the passion for Kabuki theater, here revealed by prints, masks and musical instruments. An additional set of porcelain objects proves Japanese engagement with ancient Chinese technologies and forms of knowledge. These items – especially the so-called Imari porcelain, named from the port that traded in objects made in the kilns of Arita – were produced for Japanese export from the 17th century onwards.

The museum houses a rich collection of Japanese weapons from the 15th to 19th century, including precious blades of katana and wakizashi and two armours

of Samurai. They can be observed at the third floor of the museum, along with a selection of sculptures, pots and other artifacts aimed to testify the Japanese religious tradition and the cults and rites of Shintoism and Buddhism.

The west looking for the Far East

Beginning in the 16th century, the Portuguese, Spanish and Dutch Empires waged a fierce competition for the domination of the seas and the rich trade with eastern Asia, especially China. While the Silk Road was the first point of European contact with Asian civilizations in the ancient and early modern world, the modern era saw the rise of marine navigation that favoured knowledge of artifacts coming from countries that had developed their own cultural traditions independently of Europe. The end of Japanese isolationism with the reopening of trade to other parts of the world in 1858 signalled an additional influx of objects to Europe and the rise of the phenomenon called Japonisme. During the second half of the 19th century painters, sculptors, architects and manufacturers of Western furnishings renewed their models and repertoires leaning on the knowledge of Japanese porcelain, prints and

paintings.

A visit to the Museum of Far Eastern Art means extending our own knowledge beyond an eurocentric vision and find out why such artists asManet and Van Gogh loved passionately the Ukiyo-e prints.